Approach to Clinical Diagnosis

(Adapted from Arthritis: A Diagnostic Approach, Nader A. Khalidi and John O’Neill, Chapter 2, Essential Imaging In Rheumatology, Springer 2015)

- Arthritic disorders come in many different forms, and the key to specific diagnoses is in the meticulous taking of a history and performance of a physical exam. This will decide the type and extent of laboratory investigations and the choice of imaging techniques.

- Confirming that symptoms are originating from the musculoskeletal system and are not referred, which may occur with neurologic or vascular disease, is essential.

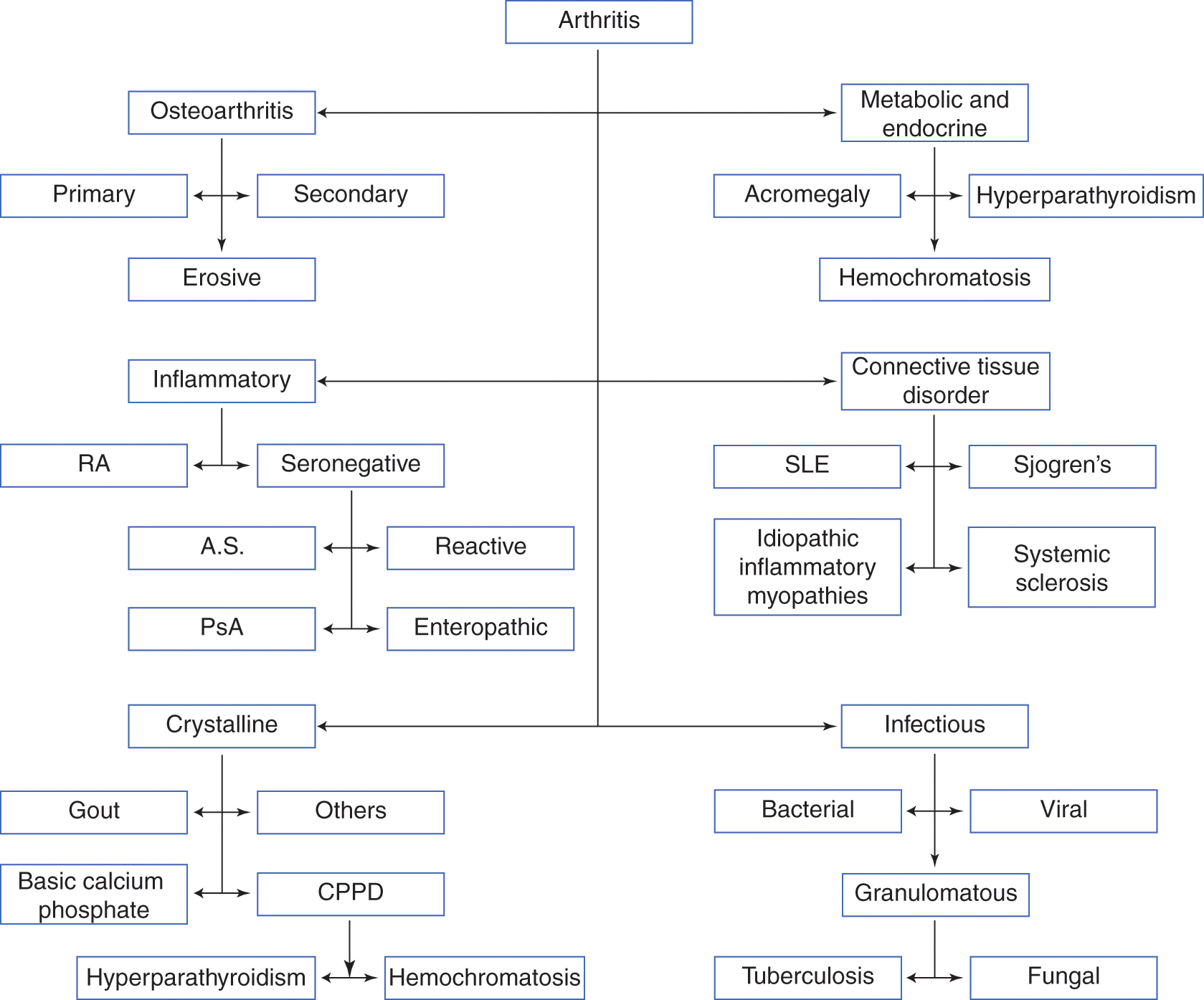

- There are many types and subtypes of arthritides(Fig1). Some of the more common arthritides that are important to keep aware of at all times include the following:

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Seronegative arthritis (ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, enteropathic arthritis)

- Crystalline arthropathies (gout, CPPD)

- Connective tissue disorders (SLE/scleroderma/ polymyositis/dermatomyositis/Sjogren’s)

- Vasculitis

- Infectious arthritis

Symptoms

Image interpretation should not be isolated and should be performed in conjunction with available clinical data. One must differentiate the underlying etiology of joint symptoms; the major differentials include inflammatory and mechanical etiologies. Inflammatory conditions typically are worse in the morning with stiffness lasting more than 60 min and improve with movement. Mechanical and degenerative arthritides on the other hand last less than 60 min and are worse with movement. The number and symmetry of joint involvement are helpful in determining the type of arthritis.

Typically arthritis is separated into monoarticular (one joint), oligoarticular (two to four joints), and polyarticular (more than five joints) types (see ‘Differential Tables’ next page). That being said, many arthritides can involve any number of joints, but typically fall into one category. Gout and CPPD are inflammatory arthritides that usually start as monoarthritis as does osteoarthritis, but as time passes, other joints can be involved. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) can have many different presentations including monoarthritis and polyarthritis, which may or not be symmetrical.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the classic inflammatory arthritis with a symmetric polyarthritis that almost always involves the hands. Assessment of synovitis, a process whereby the synovial membrane of a joint is inflamed, is important. It is the mainstay of inflammatory conditions and occurs much more often than in osteoarthritis where it is much less intense and much less widespread.

The onset of clinical symptoms can be helpful when trying to narrow down the diagnosis to a particular disease. RA is typically subacute occurring over weeks to months rather than days. Osteoarthritis is of gradual onset, usually over many years with slow progression. Crystalline arthropathies, such as chronic CPP arthritis, can also present like osteoarthritis. Septic arthritis and acute crystalline arthritis can present acutely with rapid progression of symptoms in a matter of hours.

Weakness is another symptom that is important to further clarify. This may be subjective as in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica, where the stiffness can be so great as to cause a feeling of weakness, and when questioned, some patients state that it affected them so greatly that they had to crawl to get out of bed. However, when tested objectively, no weakness is found. This subjective stiffness and pain is symmetric and proximal. In the case of polymyositis, however, the patient has very little stiffness but is both subjectively and objectively weak when tested in the proximal musculature (shoulder and hip girdle). Weakness may alternatively be neuropathic in nature, is more often distal in nature, and is associated with other neurological symptoms.

Family history becomes particularly important when looking at the group of disorders called the seronegative spondyloarthropathies (seronegative arthritis) as they occur much more commonly in HLA-B27-positive families as well as the associated disorders of inflammatory bowel disease.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Differential diagnosis of common causes of acute monoarthritis

- Infectious (bacterial, viral)

- Crystalline

- Traumatic

- Seronegative spondyloarthropathy (PsA, reactive)

- Hemarthrosis

-

Differential diagnosis of common causes of chronic monoarthritis

- Infectious (TB, fungal, Lyme)

- Seronegative arthritis (reactive, AS, PsA, enteropathic)

- Noninflammatory (OA, AVN)

- Pigmented villonodular synovitis

- Foreign body synovitis

-

Differential diagnosis of common causes of oligoarthritis

- Infectious (bacterial endocarditis, nongonococcal, disseminated GC, viral)

- Postinfectious (reactive, poststreptococcal)

- Seronegative arthritis (reactive, AS, PsA, enteropathic)

- Oligoarticular presentation of atypical inflammatory arthritis (RA, SLE, adult onset Still’s)

-

Differential diagnosis of common causes of acute polyarthritis

- Infectious (viral)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Early disseminated Lyme

- Bacterial endocarditis

- Psoriatic arthritis

-

Differential diagnosis of common causes of chronic polyarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- SLE

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Other connective tissue disorders

- Polyarticular gout

- CPPD (pseudo-RA)

- Sarcoid arthritis

- Vasculitis

- Sarcoid arthropathy

Axial Versus Peripheral Involvement

Peripheral involvement can include specific patterns like distal and proximal interphalangeal involvement (DIP/PIP) in osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis or proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joint (PIP/MCP) involvement in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, SLE, and pseudo-RA (crystalline arthropathy of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate or CPPD). Acute involvement of one joint that is red, hot, and swollen should trigger one to think of a septic arthritis, gout, or pseudogout.

Axial involvement can help narrow the type of arthritis down as well. Lower back involvement is not a characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis, gout, SLE, or systemic vasculitis but is mandatory in that of ankylosing spondylitis. Peripheral involvement with axial involvement could mean osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, or reactive arthritis. Involvement of the cervical spine is frequent in rheumatoid arthritis as well as osteoarthritis.

Other Features

Systemic features can often point to a more definitive rheumatic etiology and these features should actively be sought after. Constitutional features of fever, anorexia, weight loss, and fatigue are more associated with an inflammatory process. Nonarticular features such as a history of bloody diarrhea or a genitourinary infection can be highly associated with an inflammatory bowel disease and enteropathic arthritis or that of a reactive arthritis respectively. Specific symptoms of dry eyes (xerophthalmia) and dry mouth (xerostomia), Raynaud’s, and specific rashes such as malar, discoid (systemic lupus erythematosus), Gottron papules, shawl sign, V-neck sign, mechanic’s hands, and heliotrope rash (dermatomyositis) can help clinch the diagnosis of a connective tissue disorder. Digital ulcers, puffy fingers, and Raynaud’s are all highly suggestive if not diagnostic of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma).

Laboratory Assessment

The lab is an integral part of confirming or refuting the preliminary diagnostic possibilities that have been initiated in the history and physical examination of a patient. Differential diagnoses are often narrowed to a single diagnosis after both a careful choice of laboratory investigations and radiologic undertaking.

Inflammatory markers such as an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein are almost confirmatory of an inflammatory arthritis when they are found to be elevated. One must be cautious, however, of the nonspecific nature and the need to rule out infections and malignancies as ESR and CRP are found in these conditions as well. Conversely while it is rare to see a normal ESR and CRP in rheumatoid arthritis, it is more often than not the case in the seronegative spondyloarthropathies.

More specific testing such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) helps confirm the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis in the right clinical context. Rheumatoid factor can, however, be found in both other rheumatologic (e.g., Sjogren’s and SLE) and non-rheumatologic conditions (sarcoidosis, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis). A low-titer positive RF can be seen with aging. Anti-CCP is much more specific but again can be found rarely in scleroderma and psoriatic arthritis, so the whole picture should be looked at rather than simply the results of the lab testing.

Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) are typically found in the group of connective tissue disorders (CTD). In fact, a negative ANA should strongly suggest the search for another disease process (although rarely can be negative). ANA is positive in virtually all cases of SLE and systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), whereas in polymyositis and dermatomyositis, it is not absolutely necessary. A positive ANA in low titers can be found in the elderly. Specific antigens and patterns are related to certain subtypes of CTD but are not universally found like the presence of the ANA itself. Anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm are highly specific for SLE as that of anti-Jo-1 is of polymyositis (especially with interstitial lung disease), anti-Scl-70 for diffuse systemic sclerosis, and anti-centromere for limited systemic sclerosis. It is not unusual to see multiple antibodies in SLE (like chromatin, SSA, SSB, RNP, and Sm/dsDNA all at the same time). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are those that react with the cytoplasmic granules of neutrophils and are almost exclusively found in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) or microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) or less commonly in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA)). The patterns of the ANCA can be cytoplasmic (c-ANCA) related to the antigen serine proteinase 3 (PR3) or perinuclear (p-ANCA) related to the antigen myeloperoxidase (MPO). All other ANCAs are not really clinically relevant and so are not typically commercially available.

Arthrocentesis

- Arthrocentesis remains a critical assessment tool in spite of all the advances that have been made in other laboratory assessments in rheumatology.

- There are very few contraindications to aspirating a joint (one of them being overlying cellulitis in order to prevent introduction of an infection into the joint).

- An acute, idiopathic inflammatory monoarthritis should always be aspirated to assess for a septic joint versus an acute crystalline arthropathy. Arthrocentesis is the only way to unequivocally prove an infection or the presence of gout or pseudogout.

- If synovial fluid analysis reveals an extreme elevation in WBC, mostly neutrophils with a positive gram stain, and no crystals, antibiotics should be initiated pending culture results.

- Remember though that a patient can have an infection that coexists with a crystalline arthropathy or a crystalline arthropathy can be present in any of the inflammatory polyarthritides, and careful review of the clinical history along with the synovial fluid analyses is paramount.

Imaging

Conventional Radiography

- This is the starting point for evaluation of all arthritides as radiographs are readily available, inexpensive, and offer excellent spatial resolution.

- Standard views should be obtained in at least two projections.

- Additional views may also be required for some joints, such as the Norgaard (ball catcher’s) view, which are important in looking for erosions of the hands, e.g., radial aspects of the metacarpal heads, which may not be visible on the AP or lateral radiographs.

- Occasionally asymptomatic joints should also be imaged as they may present additional helpful findings, e.g. bilateral feet radiographs may demonstrate asymptomatic erosions in suspected RA patients.

- Radiographs can also localize pathology that can then be assessed with other imaging modalities if clinically indicated. Radiographs can demonstrate pathology, e.g. chondrocalcinosis, and distribution patterns that may be difficult to appreciate on alternate imaging.

Ultrasound

- Ultrasound has developed rapidly in the last decade in assessing patients with inflammatory arthritis, particularly in rheumatoid arthritis

- It is becoming an adjunct to the clinical examination with increased direct use in the rheumatology office

- The use of power Doppler has allowed for more effective analysis of synovitis and erosions in superficial joints. This allows for confirmation of active disease and allows the rheumatologist and patient to make informed decisions on treatment on the same outpatient appointment.

- Ultrasound can also assess for joint effusions and tendon and tendon sheath pathology and can assess multiple joints at the same setting.

- However, ultrasound is operator dependent and has a long learning curve. As such, many rheumatology centers are developing alongside dedicated musculoskeletal imaging centers.

Computed Tomography (CT)

- CT scans offer excellent spatial resolution. It is the gold imaging standard in the assessment of erosive disease.

- Its general use, however, is limited by its significant radiation burden and the availability of ultrasound and MRI.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- This technique offers excellent soft tissue contrast

- MRI can determine the extent of synovitis, pannus, effusions, and tendon and tendon sheath pathologies as can be demonstrated on ultrasound

- MRI is not however limited to detailed assessment of superficial joints. In addition MRI can delve beneath the bone cortex, a limitation in ultrasound. Bone marrow edema and pre-erosive disease can be readily appreciated.

- MRI is usually limited to evaluation of a single region, e.g., MRI of the hand and elbow requires two separate bookings due to time requirements and the field of view, which is balanced against image resolution, whereas ultrasound can image multiple joints at the same examination.

Scintigraphy

- Radionuclide bone scans are not as popular as they once were since the more widespread introduction of the MRI

- They were used historically to evaluate the distribution of arthritis in different joints.

- To distinguish infections from inflammatory arthritis, indium-labeled leukocytes or gallium scans can be employed.

- It can be useful in determining the activity in patients with Paget’s disease of the bone.